Christmas in Spain is not a “one-day event.” It is a full Christmas season that unfolds across weeks, shaped by catholic tradition, older winter customs, and family rituals that feel both sacred and lively. In many homes, Christmas celebrations begin long before Christmas Day, and the real finale arrives with the three kings on January 6.

What makes Spanish Christmas so memorable is the way it mixes layers of history: ancient Roman winter habits, medieval life, deep catholic heritage, and modern touches like the Christmas tree and even Santa Claus (or Papá Noel) in some households.

PART I —The Ancient Origins of Christmas in Spain

Long before Christmas became a Christian feast, winter in Spain was already a time of ritual, symbolism, and shared celebration. Ancient Roman customs, seasonal beliefs, and early spiritual practices shaped how people understood light, renewal, and community during the darkest days of the year. These early traditions laid the cultural groundwork for what would later become Christmas in Spain.

1) Before Christmas: Winter Festivals, Evergreens, and the Roman Mood

To understand Christmas in Spain, it helps to begin before it was even called Christmas.

Long before churches, midnight bells, and nativity scenes, winter was still a season that demanded meaning. The days were short. Harvest was over. People wanted light, warmth, and reasons to gather. In Roman Hispania, that feeling became a festival atmosphere through Saturnalia, a winter celebration linked to feasting, social looseness, and gift-giving. That Roman “winter joy” helped create the emotional foundation of what later became the holiday season in Spain.

One of the easiest examples to picture is decoration. Romans used evergreens in winter because they stayed green when everything else looked dead. That habit, tied to ancient winter festivals, is one reason evergreen decoration later felt “natural” during the Christmas season. Over time, those evergreen traditions helped the idea of the Christmas tree make sense in many places, even if Spain historically leaned more toward the Belén.

So when we talk about Christmas traditions today, some of their “feel” comes from these older winter habits: the idea that families gather, homes become warm and bright, and something symbolic—green branches, candles, shared food—pushes back against winter darkness.

2) Ancient Gift Habits: From Roman Sportula to the Christmas Basket

Ancient roots are not only about decorations. They’re also about what people give.

In Roman society, there was a practice of distributing food items in baskets, historically known as the sportula. Over centuries, that type of “food-basket gifting” echoes in the later Spanish custom of the Christmas Basket (Cesta de Navidad)—a seasonal gift packed with edible treats. The shapes and contents changed, but the core idea stayed familiar: during winter, communities reward loyalty, show care, and share food.

This is one of the most important “ancient-to-modern” bridges in Christmas in Spain: food is not just food. It is a symbol of protection, prosperity, and connection. And that connects strongly to the way Spanish families approach Christmas now—through meals, sweets, and gathering rituals that repeat every year.

3) Christianity Arrives Early, But Christmas Takes Time

Christianity reached the Iberian Peninsula very early (1st–2nd century). But that does not mean Christmas instantly became the center of life. Early Christianity was still forming, and different communities emphasized different sacred dates.

Over time, as Christianity spread more deeply and structures strengthened, the celebration of Christ’s birth became more defined. The story of the Nativity gradually moved into the center of the winter period. This is where Spain’s later Catholic tradition becomes crucial: Spain did not treat Christmas as only a social party. It built a spiritual season around it.

When the Visigothic kingdoms unified religiously under Catholicism (6th–7th century), the Christian identity of the peninsula became more publicly structured. That helped Christmas grow into a major shared celebration. By the Middle Ages, Spain had developed a rich Christmas culture: liturgy, rituals, and performance-like traditions that made the Nativity story visual and emotional.

4) Al-Andalus, Medieval Spain, and Why Spanish Christmas Food Feels “Old”

When people talk about Spain’s past, they often forget one key truth: Spain’s culture is layered. The Christmas customs you see today blend influences from ancient Roman pagan traditions, medieval al-Andalus culture, deep Catholic heritage, and modern secular elements.

That blending shows clearly in typical christmas food.

Take turrón. Its story reaches back more than 1,000 years to Muslim Spain. While today it is a classic sweet of the Christmas season, its deeper roots reflect medieval confectionery culture. In modern Spain, turrones sit beside other traditional sweets like polvorones and pestiños, creating a Christmas table that feels both religious and historical at the same time. In regions like Andalusia, roasted lamb is a traditional Christmas dish, reflecting the deep historical roots of Spanish Christmas cuisine.

This is why the ancient roots matter: even when Spanish families “just eat sweets,” they are unknowingly repeating a very old Mediterranean tradition of winter treats and preserved flavors.

5) The Nativity Story Becomes the Center: Belén, the Holy Family, and Village Life

If there is one symbol that defines Spanish Christmas, it is the Belén.

In many countries, the Christmas tree is the main decoration. In Spain, it may appear too, but the emotional center is often the nativity scenes. These are not only religious displays. They are little worlds.

A Spanish belén typically features the Holy Family, including Virgin Mary, Joseph, and the Baby Jesus, but it does not stop there. Families place shepherds, animals, bakers, water carriers, and figures representing village life. That detail matters because Spanish nativity scenes are not only “about Bethlehem.” They also reflect how Spain imagines community.

Belén scenes vary by region in Spain, reflecting local artistic styles and history. The figures might look different in Catalonia than in Andalusia, and the “landscape” might resemble the local imagination more than the Middle East. That is part of why the Belén became a national tradition: it was flexible, artistic, and deeply human.

And there is a powerful ritual connected to it: the figure of the Baby Jesus is traditionally placed in the manger at midnight on Christmas Eve. Families often place the Baby Jesus in their Nativity scenes at midnight on Christmas Eve after returning from church. That moment becomes the spiritual “switch” that turns December into Christmas.

It is also why Christmas Eve carries so much weight in Spain. It is not just dinner. It is the night when the story becomes “real” in the home.

6) Royal Influence: How Monarchs Turned Christmas into Public Culture

Spain’s Christmas identity was shaped not only by villages and churches, but also by royal culture.

- The Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, promoted Autos Sacramentales—religious plays performed at Christmas. These theatrical works later became ancestors of the Belén viviente (living nativity scenes).

- King Philip II (16th century) loved nativity scenes and brought Italian artisans to Spain. That helped transform the Belén into a respected national art form.

- Charles III (18th century) made Christmas nativity culture more civic and revived public markets at Christmas time, which evolved into today’s Christmas markets.

This matters for ancient roots because it shows how the Nativity story moved from private faith to shared public experience. Spain didn’t only “believe” in Christmas. It performed it through plays, crafts, markets, and community life.

7) Ancient Music Still Echoes: Villancicos and “Riu Riu Chiu”

Spain claims one of the world’s oldest Christmas carols: “Riu Riu Chiu,” a 16th-century villancico from the Spanish Renaissance court.

Villancicos were originally village songs, not necessarily religious at first. Over time, they became central to Christmas celebrations. Even now, families still sing Christmas carols at school events, church gatherings, and family nights at home. These Christmas songs and traditional Christmas songs help create an atmosphere that feels timeless.

So when Spanish children sing carols, they are continuing a tradition that has moved through centuries—changing in melody, but keeping the same emotional job: turning winter nights into something warm.

PART II — Christmas in Spain Today: The Calendar of Tradition

Spain’s Christmas in Spain celebrations extend from the Immaculate Conception on December 8 to Epiphany on January 6, encompassing far more than December 25. Many Spaniards actively participate in these traditions, reflecting the widespread cultural importance of the Christmas season.

Below is the classic Spanish timeline, with every key date and tradition you listed.

December 8: Immaculate Conception and the Spiritual Start

December 8 is the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, a major date in Catholic Spain. It honors the purity of the Virgin Mary and helps set the tone for the season. In many areas, Advent in Spain is marked by traditions that combine devotion with community life, including special church services.

For many families, this date signals the true beginning of the Christmas season and the broader holiday season.

December 22: The Christmas Lottery and When Christmas Celebrations Begin

In Spain, Christmas celebrations begin unofficially on December 22 with the Spanish Christmas lottery, known as Lotería de Navidad or El Gordo.

This is not just about money. It is a cultural ritual that pulls the country into a shared moment. The draw is famously sung by children from the San Ildefonso School. People buy a lottery ticket, follow the winning numbers, and celebrate together—often in groups, because many tickets are shared.

Even families who never gamble still treat the day as a “now it’s Christmas” signal. It is one of the clearest examples of how Christmas in Spain is a season, not a day.

December 24: Christmas Eve, Nochebuena, and the Special Meal

Christmas Eve in Spain is celebrated on December 24 and is called Nochebuena. This night is as important as Christmas Day because it is when families gather in the strongest sense.

Spanish families gather for a special meal on Christmas Eve, when families eat together, typically including seafood, turkey, and other meats. This is the famous Christmas Eve dinner—a long table, slow conversation, and a feeling that the home becomes the center of the world for a few hours.

After dinner, many families attend a special midnight mass called the Misa del Gallo, which is one of the most cherished services of the year in Spain.

When families return home in the early hours, many families place the Baby Jesus into the manger of their nativity scenes at midnight, marking the beginning of Christmas in the home. In some households, someone might even whisper, “es noche de dormir,” because after the sacred moment and the long dinner, rest finally arrives.

December 25: Christmas Day, Family Meals, and Lively Homes

Christmas Day is celebrated on December 25 in Spain to honor the birth of Jesus.

Spanish families prepare fresh, abundant meals for Christmas Day. A large midday lunch is the centerpiece of the celebration, and the menu varies by region. Turkey may appear in some homes, but roast meats, seafood, soups, and traditional regional dishes are just as common.

Homes are lively, full of conversation, children, laughter, and long hours spent around the table. While many families gather mainly with immediate relatives, the atmosphere is warm, social, and festive rather than calm or reflective.

The Belén (nativity scene) remains an important presence in the home, and the religious meaning of the day is respected. However, the focus is very much on sharing food, time, and joy together.

In Spain, Christmas Day is about celebrating life, family, and tradition, with a table full of freshly cooked food and a house full of people.

Christmas Food: Turrón, Barquillos, and the Flavours of the Season

Christmas in Spain has a very distinctive taste, and it is a sweet one. During these weeks, homes are filled with traditional treats that appear only at this time of year.

Turrón is the undisputed star of the season. Made mainly from almonds, honey, sugar, and egg white, it comes in many varieties. The most traditional are turrón de Jijona, soft and creamy, and turrón de Alicante, hard and crunchy. Today, tables also include chocolate turrón, toasted almond versions, and modern flavours, but the classic bars are always present.

Alongside turrón, families enjoy polvorones and mantecados. These crumbly sweets, often dusted with powdered sugar, are traditionally eaten by gently pressing them before unwrapping. Their flavour and texture are deeply linked to Christmas memories in Spanish homes.

Barquillos, thin rolled wafers, add a light and crunchy contrast to richer sweets. They are often shared after meals or offered to guests with coffee or liqueurs.

Another seasonal favourite is churros con chocolate. This is not a dessert tied to a single day but a ritual of the season. People enjoy churros after late-night walks, after Midnight Mass (Misa del Gallo), or on festive mornings when the streets are still quiet and cafés are just opening.

In Spain, food is never “extra.” It is the social glue of Christmas. Families plan these sweets and meals in advance because Christmas is not one celebration but a season of repeated gatherings, open tables, and constant sharing.

December 28: Día de los Santos Inocentes and Pranks

On December 28, Spain celebrates el Día de los Santos Inocentes. In English, it is known as Holy Innocents Day.

This day is linked to the biblical story of the massacre of infants ordered by King Herod, which is why the term innocent saints appears in religious framing.

But culturally, the day evolved into something surprisingly playful. Today, people play pranks on one another, making it similar to April Fools’ Day in other countries. This mix—serious origin, humorous modern custom—shows how Spanish tradition can hold both memory and joy.

December 31: New Year’s Eve, Nochevieja, and the Twelve Grapes

New Year’s Eve in Spain is celebrated on December 31 and is known as Nochevieja. In everyday conversation, people may also casually refer to it as New Year’s Eve, especially in international or informal contexts. The celebration is also commonly referred to as ‘year’s eve’ in some contexts.

As midnight approaches, families and friends gather around the television or in public squares to follow the twelve chimes of the clock. With each chime, people eat one grape, a tradition believed to bring good luck for each month of the coming year. Successfully finishing all twelve grapes before the final chime is part of the fun and challenge, and it is one of the most recognizable rituals in Spanish culture.

Nochevieja is both festive and symbolic. It marks the end of the year with shared rituals, laughter, and anticipation, often followed by late dinners, parties, or celebrations that continue into the early hours of January 1.

Although it welcomes the New Year, Nochevieja is still very much part of the Spanish Christmas season. The celebrations continue beyond December 31, remaining alive until January 6, when the arrival of the Three Kings brings the festive calendar to a close.

Santa Claus vs. the Three Kings: Modern Change, Ancient Core

In recent decades, the modern tradition of Papá Noel (Santa Claus) has gained popularity in Spain, especially in larger cities and in households influenced by international media and global culture.

As a result, some families now choose to exchange gifts on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day, and many children may receive presents from Santa Claus in addition to other traditions.

However, for a large part of Spanish society, the Three Kings (Los Reyes Magos)—often referred to as the ‘magic kings’ for their extraordinary wisdom, star-guided journey, and the sense of wonder they inspire in children—remain the primary and most meaningful gift-bringers. Their arrival on January 6, Epiphany, continues to hold deep cultural, religious, and emotional importance.

This balance reflects the reality of Christmas in Spain today. Modern influences exist and are visible, but the ancient core of the celebration remains dominant: the Nativity story, family-centered rituals, community traditions, and the gifts brought by the Three Kings.

For both accuracy and clarity, it is important to understand Christmas in Spain as a living tradition—one that adapts to change while still placing Epiphany at the heart of the season.

January 5: Cabalgatas and the Arrival of the Three Kings

On January 5, towns and cities across Spain celebrate the arrival of the Three Kings with festive parades known as cabalgatas.

During these parades, the Kings and their companions throw sweets to the crowd, children watch wide-eyed, and the streets turn into a moving celebration. This is the moment when the “magic” of Christmas becomes public and shared.

That night, in many homes, children place their shoes near the door, balcony, or nativity scene so the Kings can bring gifts while they sleep.

January 6: Three Kings Day, Día de Reyes, and the Grand Finale

January 6 is celebrated as Día de Reyes, also known as Three Kings Day or King’s Day.

This is traditionally the day when children receive their main Christmas gifts in Spain. The Three Kings—Los Reyes Magos, also called the Wise Men—are still spoken of in many households as magical figures who travel through the night to bring presents.

Día de Reyes marks the true end of the Christmas season in Spain. In other words, Christmas here does not really finish on December 25, but on January 6.

Roscón de Reyes: The Cake with a Secret

A central tradition of January 6 is the roscón de Reyes, a special cake traditionally enjoyed on Three Kings Day.

This ring-shaped cake is shared on Three Kings Day and contains two hidden surprises: a small figurine and a dry bean. Finding the figurine is considered good luck and often earns the finder a paper crown. Finding the bean usually means paying for the cake—though rules vary by family.

The roscón turns the end of the season into one final playful ritual, offering laughter and togetherness before everyday life resumes.

Nativity Scenes, Regional Identity, and Catalan Traditions

The tradition of the belén (nativity scene) became popular in Spain more than seven centuries ago and remains central to Christmas celebrations. These scenes often portray not only the Nativity, but also village life, trades, and landscapes, blending faith with everyday culture.

In Catalonia, two distinctive traditions stand out:

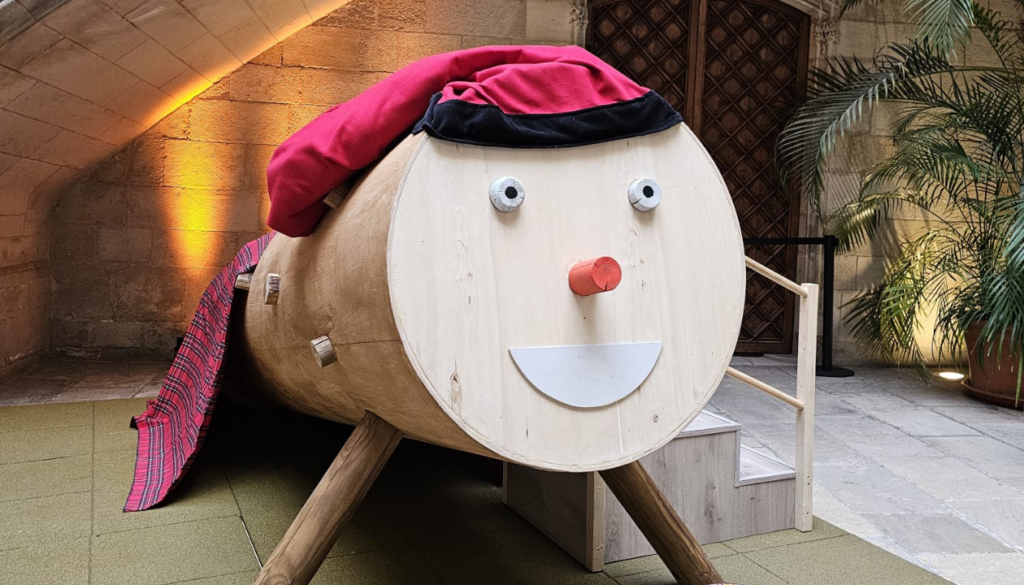

Tió de Nadal

Children feed the log, keep it warm, and then beat it with sticks while singing so it is believed to bring gifts—sweets and small presents—to children in a humorous ritual.

El Caganer

A small figurine hidden in nativity scenes, symbolizing fertility, prosperity, and the idea that all people—regardless of status—are equal.

Other regions also express strong local identity. In places like the Basque Country, Christmas may include local characters and customs, yet still fits within Spain’s broader Epiphany-centered calendar.

Experience Spanish Christmas as a Season, Not a Single Day

Spanish Christmas isn’t only something you watch or read about—it’s something you feel through repeated family gatherings, long meals, village traditions, and the build-up to the Three Kings. When you understand the language inside these customs, the season becomes more personal, more human, and far easier to connect with.

👉 Explore our Spanish Homestay Immersion Programme (SHIP) and experience Spanish culture in real daily life—where traditions like Nochebuena, the Christmas lottery, and Día de Reyes are part of normal conversation, routine, and community.

It’s a meaningful way to learn Spanish through the moments Spaniards care about most.

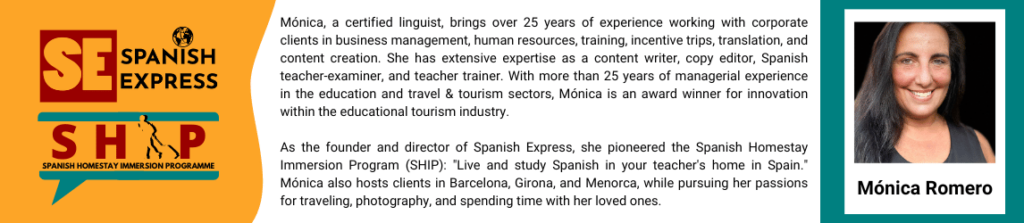

Get in Touch With Our Founder and Director

If you’d like help planning the right immersion experience or choosing the best time to learn Spanish through culture, you can reach our founder directly:

Mónica Romero

Founder and Director, Spanish Express

📞 Phone / WhatsApp: +44 7903 867894

📧 Email: monicaromero@spanishexpress.co.uk

¡Feliz Navidad y próspero año nuevo!